March 1st

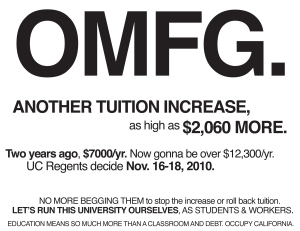

The regents think it’s a great idea. Blumenthal is beside himself. It’s so great that the students are mobilizing to go to Sacramento. Student leaders are excited: the regents are with us! Sacramento must listen!

On the regents’ side, it’s perfect. The shift to Sacramento solves two problems that the student movement poses. First, it gets the students off of their backs, displacing the anger further up – an age-old tactic of bureaucrats. The removal of antagonism between students and regents allows them to declare themselves on our side, which they of course could not do with the occupations or campus blockades, or when they needed busloads of riot cops with tear gas guns just to hold a “public” meeting. Second, it incorporates the movement, keeping it confined to sanctioned action. As soon as a coalition of student leaders, faculty, unions, and (oh how wonderful) administrators unites in Sacramento, the path is clear: lobbying, symbolic demonstrations, cliché-as-fuck chants and picket signs: in short, a managed movement.

Just as the university pits students against workers, making them compete for limited resources, so the state is now pitting all university stakeholders against prisoners and potentially against all other public programs. UCSA, the system-wide student government, is perfectly content to play this game, calling for a “March for Higher Education” starting with March 1st in Sacramento. Yes, the title is annoyingly snappy, but notice too that their version of the movement is reduced entirely to fighting for “higher education.” A mobilization that grew from a statewide conference of students, teachers, etc. from all levels of public education — an effort to build solidarity in order to combat the state’s divide-and-conquer techniques — is now being commandeered to push for a slightly larger share of the pie for our little divided-and-conquered sector. UCSA accepts and promotes the “we all have to compete for ever-decreasing resources, so we should do our best to get ours” logic. Most of the media does not even mention the component of the movement that is outside of “higher education” or outside of education entirely. But as long as this remains a student movement, it will do nothing more than what student movements invariably do: try to make the educational system marginally better for a little while. Those in power can use this tactic to the extent that we are divided: as long as there is only a student movement, no matter how strong it may be, it can easily be displaced, appeased, and absorbed.

The question, then, is whether we need/want fundamental change or just the reactionary reform that will get us partway back to the greatness of the UC in the 80s or the 60s. Another aspect of the same question is whether the administrators and politicians are with us – that is, benevolent, well-intentioned (if misguided in their policy decisions) workers who, with our constructive input and a lot of compromise, can help us improve things — or whether they are objectively opposed to us and our interests, inevitably an obstacle to any worthwhile goals (free education, free society, etc.).

It is becoming increasingly clear to most students that their education is going into the shitter, yet many still cling to the idea that the regents, as well as state legislators, are doing their best in a bad situation. They call us cynical for acknowledging that these powerful men can never give us what we need, but really they are the cynics, for it follows from their logic that education could not get much better than it is now: despite the best effort of so many intelligent, good people, nothing can be fixed.

It’s not difficult, however, to see that power serves itself — that those in power (and their representatives) will tend to make decisions that reinforce their own power — and that their very position opposes them to us. All one needs to do is listen to their words.

The Regents

“Students are a legitimate voice. [Students] are there as a consumer, and we are seeing if our product is fulfilling your needs,” said chairman of the board of Regents Russel Gould (emphasis added). Rarely do we see such a blatant expression of the market logic with which they govern the university. Of course it shouldn’t be surprising — Gould, like most regents, has years of experience as a CEO (Wachovia is his most recent gig, and he’s made millions from the bailouts — see the 2009 Disorientation Guide). And nobody can deny the capitalistic nature of the modern university system: he runs it like a business because it is a business. However, he does not admit the flip side of the knowledge-market game: we are not just consumers, but also producers in this all-encompassing system. Like workers in 19th century factory towns owned entirely by the capitalists – where employees work in the company factory, live in company housing, shop at the company store, etc. – our lives are entirely monopolized by the university system.

We are paying to receive knowledge, while at the same time we are the producers of knowledge. Maybe professors do more of the ‘production’ while undergrads do more of the ‘consumption,’ but before one can teach or research or write one must pay to study for 4 or 5 or 10 years. In any case, it’s not as if students simply pay professors to teach them. Rather, there is a whole array of mediations, allowing a massive university bureaucracy to arise, allowing funding bodies to control research, allowing profits to be made at every level — from books to loans to standardized testing. The university employs an integrating strategy: all production and circulation of knowledge must pass through it; our desires to learn and to teach are forced into an increasingly privatized (that is, profitable) system.

Many students recognize that they could learn just as much by simply reading and discussing with their peers. Programs like the community studies field study program, which give credit for basically doing non-academic work independently, are praised as innovative. We recognize independent study as “a good deal” compared to traditional classes – less work, more flexibility, taking the classroom out of learning. Thus the tendency toward providing nothing. We know that self-directed learning is more effective and enjoyable than passive receipt of information, but then why do we need the university at all? Despite their talk, anyone who is a student (myself included) is unwilling to give the decisive “fuck you” to the university and drop out. Of course this is because what they want to do, what they want to be, does not depend primarily on knowledge, experience, etc. but on the degree. Academia is a closed system. It exists as a complex spreading out from universities into industry, government, and even social life. Knowledge without the degree gets you nothing; all paths lead through them.

The university system has monopolized knowledge, enlightenment, and even social advancement. Like the rest of the private (and public!) spheres, they have isolated a realm of desire and capitalized on it. The rulers of education are simply knowledge profiteers…

Schwarzenegger

“What does it say about any state that focuses more on prison uniforms than on caps and gowns?” asked Schwarzenegger recently. “It simply is not healthy.”

He takes his rhetoric directly from the movement. And activists can pat themselves on the back since, according to his chief of staff, Susan Kennedy, “Those protests on the UC campuses were the tipping point.” Never mind that the budget increase will never make it through the Legislature, as ex-chairman of the Board of Regents Richard Blum (among others) has confirmed. The significant thing here is that state politicians, just like the regents, are able to win popularity and de-escalate the movement by simply affirming its rhetoric and making empty promises. The fact that it’s working shows that all the movement is looking for right now is a policymaker who will “actually listen” (and make empty promises).

“Choosing universities over prisons . . . is a historic and transforming realignment of California’s priorities.”

Here he attempts to appease a group that has recently gained some political influence and public sympathy — students — by fucking over a politically powerless (and sympathy-less) group — prisoners. But in reality he’s not choosing education over incarceration, he’s simply choosing to capitalize more on both. The word realignment is a misleading appeal to the widespread sense of the UC’s lost greatness. Yet he doesn’t suggest reducing tuition to even the ballpark that it used to be in. There is no hope of tuition being reduced at all, nor even of preventing the increase (and future increases, to be sure). All he is doing here is making the rhetoric of “money for education, not incarceration,” fit with a neoliberal agenda — i.e. privatize everything.

But as always, only the profits are privatized — the costs are still socialized. Perhaps taxpayers will spend less on prisons, but that money will simply be invested in the university system, which has proven to be extremely profitable for private capital, especially in recent years. As professor Bob Meister’s excellent letter to students, “They Pledged Your Tuition,” explains, the tendency of the university in recent years has been to spend more on construction, development, and other investor-friendly activities (see http://www.cucfa.org/news/tuition_bonds.php). More than the scandalous amount paid to execs, the real drain on university funds is the constant flow of capital out into the private sphere. The regents vote to build more shit, the university sells bonds (backed by your tuition) to private investors to raise capital, transfers that capital to whatever company is contracted, and then pays back the bonds with state and/or tuition money. This is happening as we speak, as we struggle. The SF Chronicle has reported on the outrage that the regents voted to increase executive salaries during the same meetings in which they cut key programs and implemented furloughs. What they neglected to report was that at those same meetings they also approved new multi-million dollar construction projects funded by selling bonds. But putting a stop to expansion, of course, is not on the table, for no matter how tough things get, the university must remain profitable (if it weren’t, they would have a real crisis!). Schwarzenegger’s plan simply ensures this profitability and ensures investor confidence, while at the same time paving the way for increased profits in the prison industry.

A line from his State of the State address pretty well sums up how he sees us:

“The number of high technology companies that we have in California is related to how many brilliant scientists we have in our universities… which in turn relates to how many smart undergraduates we have… which is related to the number of high school students who graduate… and it goes down through the grades. That small child with the sticky hands starting the first day in kindergarten is the foundation of California’s economic power and leadership. We must invest in education.”

From the moment we enter the public sphere as snot-nosed little kindergartners, our masters see us as one thing, and one thing only: human capital.

Co-optation

Gould: “[Students and regents] have a lot of common ground.” That ground is exactly the terrain of co-optability.

One criterion to judge any struggle by is the extent to which it gets co-opted by those in power. Student regent Jesse Cheng explains the process like this: “What has happened with recent student actions has made student activism part of the equation. Regents are now saying, ‘We recognize your force, and want to be part of it.'”(emphasis added). Cheng thinks this indicates the movement’s strength, but in reality it shows its weakness.

Our revolutionary potential will be co-opted to the extent that its content is co-optable (i.e. symbolic actions, reformist demands…). It will remain unauthorized and potentially effective to the extent that its content is truly threatening. It may seem obvious (and tautological) that we will remain hostile to them as long as we take hostile action… But there is nothing else to it. Activists and revolutionaries use moralistic language to express their outrage when their movements are co-opted, whether by political parties, unions, or, in this case, by the management itself (that is, by those who are objectively opposed to us but whose power relies on the myth of their benevolence): “How could they steal our movement like that?!” “How could our comrades sell us out like that?!” Etc. The only thing that co-optation shows, however, is that our actions have failed to truly oppose the opposition. And all the more so if they ignore us — they will tend to choose whichever strategy works best for them. But when we take action that truly threatens them, they can neither ignore us nor co-opt us.

In the case of student struggles, this means strategic disruptive action. It means absolutely not respecting the authority of the administration nor the proceduralism they prescribe. The procedures that they claim must be followed if you really want to change things, are simply dams and dikes that channel oppositional potential into controlled, harmless forms. Beyond simply disrespecting the regents, chancellor, student government, etc., we must recognize them as adversaries, as would-be co-opters, and we must actively oppose them. And for our struggles to have any chance of precipitating real change, action must go beyond the university, taking on forms that counter their pathetic attempts at displacing the burden onto less organized, less powerful parts of society.

The Crisis

We are not interested in questions of responsibility, of who is to blame — at the university, state, national, or world level — for the current crisis. Technically, we have as much responsibility as anyone else, just by virtue of having desires. We should be proud. Just by living and breathing and having human needs, we threaten the system that idealizes mindless production and consumption.

Capitalism cannot solve the problem of our existence. What has transpired is neither poor management by benevolent policy-makers nor the unchecked greed of so many bad men. Rather, it is the inevitable manifestation of a fundamental insolvency. We are not interested in how to manage the crisis, nor do we care whose fault it is, nor can we accept any partial solutions. There is no solution without removing the contradiction at the heart of the crisis. From the point of view of those in power, resolving the contradiction would require learning how to dehumanize humans – to fully mechanize and atomize production and the producers themselves. From our perspective, overcoming the contradiction requires not only making education free, but overcoming capitalist relations as a whole. We cannot solve the crisis within the current system because we are the crisis of the current system.

Thus we should move from questions of should we fight? to how do we fight? We have seen that the most tempting routes — those that will attract the most media attention, win the widest public support, and feel the most inspiring — will end up working to the advantage of our enemies. We should remember some of Marx’s words on the subject of creating lasting change:

“Bourgeois revolutions . . . storm swiftly from success to success; their dramatic effects outdo each other; men and things seem set in sparkling brilliants; ecstasy is the everyday spirit; but they are short-lived; soon they have attained their zenith, and a long crapulent depression lays hold of society before it learns soberly to assimilate the results of its storm-and-stress period. On the other hand, proletarian revolutions . . . criticize themselves constantly, interrupt themselves continually in their own course, come back to the apparently accomplished in order to begin it afresh, deride with unmerciful thoroughness the inadequacies, weaknesses, and paltriness of their first attempts, seem to throw down their adversary only in order that he may draw new strength from the earth and rise again, more gigantic, before them, recoil ever and anon from the indefinite prodigiousness of their own aims, until a situation has been created which makes all turning back impossible…” (from The 18th Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte; emphasis added).

I am not trying to argue that we should model a movement around any supposedly proletarian or Marxist revolution in history, nor am I saying that we need to be more proletarian and less bourgeois. But what characterizes the great bourgeois revolutions for Marx is the co-optation of revolutionary desire, action, and organizational structure by those who want only to increase their own power and to create and protect the conditions of efficient exploitation. This strategy succeeds where the revolutionaries are unwilling to destroy the old world and the new world, to destroy even what they create. We do not need to build a large, hardened organizational apparatus that can push for gradual, slow, strategic change. Our action must be immediate, radical, and collectively organized. What does need to be changed is our desire for immediate, spectacular victory. Many of us are accustomed to working with activist organizations whose particular campaigns can indeed be won in the short term. We need to untrain ourselves from this tendency and set our sights on long-term liberation. The spectacular wins of the 60s were all well and good, but they were simply rolled back and chiseled away when the political and economic climate changed.

Marching to Sacramento with the regents and the student government will certainly be well-covered in the media. It will be celebrated as historic. And that’s all it will be, and that’s all it will do.